- Home

- Rosie Price

What Red Was Page 2

What Red Was Read online

Page 2

2

Though she would never have suggested anything his mother had directed, Kate started to invite Max to come and watch films in her room. He complained about the size and speed of her laptop, though, fussing and trying to minimize the appearance of the smears on its screen. One morning during their second term, after he’d spent the weekend with his parents in London, Max texted Kate to tell her he had a surprise to give her if she came up to his room. Kate called him.

“Why do I feel nervous?”

“I promise you’ll like it,” Max said.

“Can’t you come down and show me?”

“Just come upstairs. It’ll be worth it.”

As always Max had left his door ajar, but the curtains were drawn and the lights were off. Kate pushed a pair of high heels to one side as she closed the door behind her: she wanted to know who the shoes belonged to, but she wasn’t going to ask.

“So? What do you think?” Max said.

“I think it’s extremely dark.”

“Look.” Max pulled her by the hand. The two armchairs that were normally by the window had been dragged into the middle of the room and, balanced precariously on a pile of books, a projector cast a block of white light on the wall above Max’s bed, from which he had removed the prints—one of Lana Del Rey and another of a street in Marrakesh, a gift from his mother—which usually hung there.

“I found it at home,” Max said. “My mum doesn’t need it anymore.” Kate sat down, and he went to adjust the projector, shifting the books beneath it. “Is the picture straight?”

They both looked up at the light moving slowly across the wall, as Max tilted the lens.

“It’s pretty good,” Kate said, tilting her head to one side, “I mean, if you wanted a trapezoid.”

“A trapezoid? Are you sure?” said Max. “Fuck. Wait, you hold this.”

“I have so much to do,” Kate objected; she did want to stay, but she had an essay to finish.

“This is work. We’re watching films. We can even watch foreign films.”

Kate shook her head. “It’s important. It’s for Kerrison.”

Max reached over to switch off the projector. “What are you writing about? I haven’t started mine.”

“The usual bullshit,” Kate said, shrugging. “I actually managed to use the word ‘synecdoche’ to describe the cinematic portrayal of the Parisian insect population.”

Gleeful, Max whipped the curtains open. “You’re a genius. Kerrison will be all over it.” Kate, whose last effort for Kerrison had received simply the word “WHY” written in its margin, doubted Max’s optimism. But in fact he would be proved right: Kerrison did love the essay, and Kate tried her best to look embarrassed as the last paragraph was read out to their class.

“This is the key,” Kerrison said, holding up the essay. “Write about what interests you. If you love French cinema, write about French cinema. If you have passion, your readers will be able to tell.” She flipped back a page and looked at Kate over her glasses. “And I love what you said about Zara Lalhou.”

Kate did not make eye contact with Max.

“Is it weird for you,” she asked later, “if I write about your mother?”

“Why would it be weird?” Max said. The projector was now working and they were waiting for a takeaway to arrive.

“I mean,” Kate said, “I can’t imagine you writing your dissertation on the late pottery of Alison Quaile.”

Max laughed. “Honestly, it’s not weird,” he said. “I’m kind of used to my mum being…you know. Other people’s property.”

For Max, Kate realized, it was normal to know that he might have things other people wanted, and to be so secure in his possession of these privileges that he didn’t need to guard them closely. It was from this confidence that his generosity sprung: he wasn’t worried about what he might lose because he’d always had more than enough. He was generous with his time, as well as his money. Though he was often in demand, he and Kate saw each other several times a week for most of that first year, watching films, sitting in their armchairs—which Max called their thrones—and passing wine and takeaway food, usually paid for by Max, who always seemed to forget to ask Kate for cash. As exams drew closer, and others in their year stopped going out and drinking so much, Kate and Max spent more evenings together, working only when it became absolutely necessary.

“You know what we should actually do,” Max said, on the evening before their first exam.

“Not fail?” said Kate.

“We should go to France,” Max said. “Go to France and see France and speak French. Otherwise”—he looked glumly at the pile of books on his floor—“what’s the point of all this?”

* * *

—

They finished the year with passes: Kate’s better than Max’s but worse than she’d hoped for, and two days after they’d had their results they began to pack up their rooms, ready to return home. At the beginning of July, Max paid his sister £100 to borrow her car for a week, promising to return it unmarked and valeted at the end of his holiday with Kate. They met early at Paddington Station and loaded the boot with the four-person tent she had taken from her mother’s loft. Max, who had never camped before, had agreed to do so on the condition that Kate didn’t complain if he urinated in nearby shrubbery. He had also agreed to drive on the further condition that Kate stayed awake for the whole journey, from London to Dover, and then Calais to the South of France. She had brought a six-pack of canned iced coffee and a playlist, as well as a series of complaints about her brief return home.

“She treats me like a kid, you know,” she said as they neared Dover. “Asking what I want for dinner and stuff. I’ve lived away from home for a year now. I’ve basically moved out.”

“Isn’t it a nice thing that she asks what you want for dinner?” Max said.

“You never ask me,” Kate said. “We just sort of, know, you know?”

Here Max had to concede. “We do always seem to know.”

On the ferry they bought playing cards and played Spit until Kate called time, accusing Max of being too aggressive with his technique. When they arrived in Calais, Max opened the car’s tiny sunroof and turned Chaka Khan up to full volume.

“Don’t crash,” Kate advised, as they pulled out of the terminal. Somewhere south of Clermont-Ferrand the road narrowed and straightened, and they were flanked on both sides by plane trees: it took them ten hours to get to Béziers, and then another hour to find the campsite, which was hidden behind a private estate just north of the beach. When at last they checked in they went straight to the restaurant on-site, leaving the car parked under a tree and Kate’s tent in a pile in the middle of their allocated campground.

They sat at a white plastic table drinking beer until it was dark. Pitching the tent, then, was a challenge: Max tried to floodlight their spot with the car headlights, blasting the rest of the campers with a short burst of Chaka before the engine stalled in protest. Instead, they stumbled around in the dark waving their phone flashlights and tripping over pieces of canvas until they had constructed something resembling a tent.

“Max,” Kate whispered, once they had zipped themselves into their respective compartments. Max was standing up, completely naked, his part of the tent illuminated by the lamp below him. “I can see your penis.”

“How?” Max whispered urgently.

“You’re up-lit,” Kate replied.

“Oh. Sorry.” Max’s silhouette, which was magnified across the canvas that separated them, put its hands over its crotch.

Kate snorted, turned so she was facing the other way. “See you in the morning,” she said.

“The Shadow of the Dick,” Max said. “Horror classic.”

* * *

—

Every morning for the next four days Kate and Max drank coffee and ate nect

arines at their dusty breakfast table, and in the afternoons they swam in the sea and lay on the sand while the salt water dried onto their skin and into their hair. Kate listened to her music, eyes closed and the sun warm on her face; she began to feel as though the wire connecting her ears to her phone was the only thing keeping her connected to the real world. Max dipped in and out of the sea, returning to sleep, or to prop himself on his elbows and read. The breeze would rise and fall, and sometimes his elbow would touch her fingertips. On the fourth day, they stayed there until the sun began to dip, and when it got dark Max went back to the campsite to get his papers, and they rolled a spliff. Lying on the sand, they watched the smoke floating above them, and Kate felt then that she too could float.

The next afternoon, they made plans to drive to a beach a little farther down the coast: there was a diving platform Max wanted to try. Kate was in the laundry room, charging her phone and watching a tanned blond man load a tumble dryer with dry, unwashed clothes, when her screen started to flash with an unknown number.

“Kate?” said the voice on the other end of the line. Kate knew straightaway who the voice belonged to, but instinctively pretended not to recognize it.

“Hello,” she said. “Who’s that?”

“It’s Zara Rippon, Max’s mother.”

It surprised Kate to hear Zara use her husband’s name, and for a moment she said nothing.

“He hasn’t been answering his phone,” Zara said.

“Oh, it’s been dead for days,” said Kate. Immediately, she regretted the metaphor: Zara was surely phoning about something serious. “Is everything OK?” she said.

“There’s been an accident,” Zara said. “Rupert, Max’s uncle. He’s fine, but he’s in hospital.”

“Oh my God,” Kate said. She paused, waiting for Zara to say more, then remembered that it was Max and not her that Zara wanted to speak to. “I’m so sorry.”

“Thank you, Kate,” Zara said. She sounded a little weary. “He crashed off the A4, into the front of the Cromwell Road Waitrose. Four times over the limit, no seat belt. Thank God nobody else was in the car. And he was only going slowly; he was swerving to avoid a sheep.”

“A sheep? In London?”

“It was actually a smear on his windshield, from what I gather. He’s conscious, but they’re keeping him in.”

“I’m so sorry,” Kate said again. She was nearly back at the tent now, but part of her wanted to stay on the phone with Zara. Instead she handed over to Max and sat down in the canvas doorway, sticking her feet out into the sun. Watching Max pace slowly along the gravel pathway, nodding as he spoke to his mother, Kate wondered if he was agreeing to change his ferry booking, arranging to come home early. But then he started laughing, shaking his head at something Zara had said. Kate couldn’t imagine laughing so freely with her own mother, and she felt a pang of envy.

“What’s happening?” Kate said, as soon as Max joined her again.

“He’s OK,” Max said. “Just an accident. He’s lucky it wasn’t worse.”

“Are you going to go and see him?”

“Yes. When I’m back.”

“Do you think you should go home sooner?” Kate moved the zip back and forth along the bottom of the tent’s entrance as she spoke. “Please don’t worry about the holiday, if you have to.”

Max looked down at her. “Why? There’s nothing I can do,” he said. “And there’s nowhere I’d rather be right now.”

Kate carried on playing with the zip, not wanting to look at him directly in case he saw too clearly her relief at his words.

“OK,” she said. “You can always change your mind.”

They drove to the next beach as they had planned, and Kate kept her phone ringer on in case Zara called again. When she told Max this he looked at her bag and shrugged, a gesture which told Kate that now was not the right moment to ask about Rupert. She hoped that Zara wouldn’t call while they were in the car, because Max would see that Kate had already saved her number in her contacts.

That night, Kate thought she would fall asleep quickly, worn out by the long drive and the heat. But as soon as she zipped herself into her sleeping bag, she was conscious of how heavy her stomach felt after their late dinner, of her thighs sticky against each other, of the hard ground against her hips, and she lay on her back looking up at the domed ceiling of the tent. Max had been distant all afternoon, and even though he was less than two meters away from her, she missed him. It was an hour or more before she rolled onto her side. She had been listening out for the sound of Max’s breathing, but could hear nothing to indicate he was asleep.

“Max,” she hissed. “Max, are you awake?”

“Yep,” Max said. He didn’t bother whispering; his voice was flat. Kate sighed and climbed out of her sleeping bag, unzipping her side of the tent. The noise was so loud she thought she might wake the entire campsite, but she did the same for Max’s compartment and climbed in with him.

“Budge up,” she said.

Max sat up grumpily. “I could have been masturbating,” he said. But he sounded less flat than he had a moment ago, before Kate had invaded his space.

“I knew you weren’t,” Kate said. “You’ve been far too somber.”

“I’m not somber.”

“You are. And that’s fine. That’s why I’m here.”

Max said nothing.

“Are you close to your uncle?”

“We used to be,” Max said. “I am still, kind of. But him and my dad.”

“Not so much?”

“No.”

Max shuffled around and turned to face Kate, who had her arms wrapped around her chest. He unzipped his sleeping bag and threw it over her, so it was half covering the two of them.

“He taught me to drive, in fact. Rupert. In Bisley, at my granny’s house. I was fifteen, and we used to take my grandad’s car around the fields. We crashed into a fence once. Well, I crashed into a fence. But I remember him getting shit for it from my dad, as the responsible adult. He was probably drunk, now I think of it.”

“How long has he been drinking for?”

“A while. Not consistently.” Max took a deep breath. “He gets down,” he said, weighing his words carefully. Kate could tell this was not something he often spoke about. “You know. Depressed. It goes in phases, but it seems to have got worse recently. I’ve no idea why.”

“There’s not always a reason,” Kate said. Max waited for more. “My mum, too. That’s why she learned pottery. I’m not saying it’s for everyone, but it seemed to help her.”

“Pottery? Really?”

“It’s just her thing. Takes her out of her head and back into the world. And I guess some people just need a bit more help than others finding their thing.” Kate paused, and when she spoke again there was a touch of pride in her voice. “I bought her a class for her birthday one year and, well.”

“I don’t know what Rupert’s thing is,” Max said. “Drinking, probably.” He laughed wearily. “That was a nice thing to do, though, Kate. For your mother.”

“It wasn’t,” said Kate, momentarily irritated by the assumption that she’d had any option other than to try to help her mother.

“I just meant you’re a nice person,” Max said.

Kate looked at Max, and softened. “So are you.”

“I’m not so sure,” he said.

* * *

—

When they parted back in London, Max went home only briefly before going to the hospital to see Rupert. He found him propped up in bed, surrounded by plastic boxes of fruit and biscuits, with a bandage around his head.

“You look like somebody who’s pretending to have a head injury,” Max said when he’d sat down next to his uncle. He reached out his hand to touch the bandage, but then thought better of it. Max had his uncle’s green-gray eyes, an

d it was a strange thing for him to see that same shade looking back at him, dulled, even if Rupert was now smiling.

“You know I expect some sympathy, now you’ve come all this way.”

“It was no effort,” Max said. “You’re not that special.”

“Well. At least you didn’t bring me any more fucking fruit.”

“It’s good for you,” said Max. They both looked at the withered stalk of white grapes and the wrinkled apricots that had been pushed to the edge of Rupert’s bedside table. There were cards expressing sympathy, and a pile of magazines.

“I can’t read those, either. Because of the concussion. Can’t even watch the football, the pixels get right behind the eyes. Like needles, honestly.” Rupert coughed and smacked his chest. “But, of course, it’s entirely self-inflicted.”

It seemed unkind to agree, so Max didn’t say anything.

“Your father is furious with me. Thinks I need to stop drinking, but…” Rupert stopped. “Where’ve you been, anyway? You look disgustingly healthy.”

“I was on holiday,” Max said. “France. Just got back.” From his pocket he took the pack of cards he and Kate had played with on the ferry, and cigarettes he had brought from Calais. “I did bring you some presents, though.”

Rupert’s eyes brightened when he saw the two packs in Max’s hand. He slipped the cigarettes straight into the drawer next to his bed before taking the cards and tapping the pack with his knuckles. “Now we’re talking,” he said, shuffling himself upright. “I hope you’re ready to be beaten, boy.”

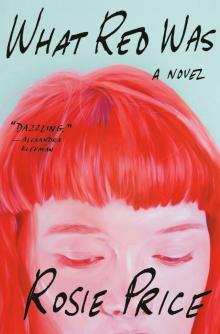

What Red Was

What Red Was